Sudo-rs dependencies: when less is better

This blog is also featured on the ISRG's Prossimo website.

Growing and shrinking our dependencies

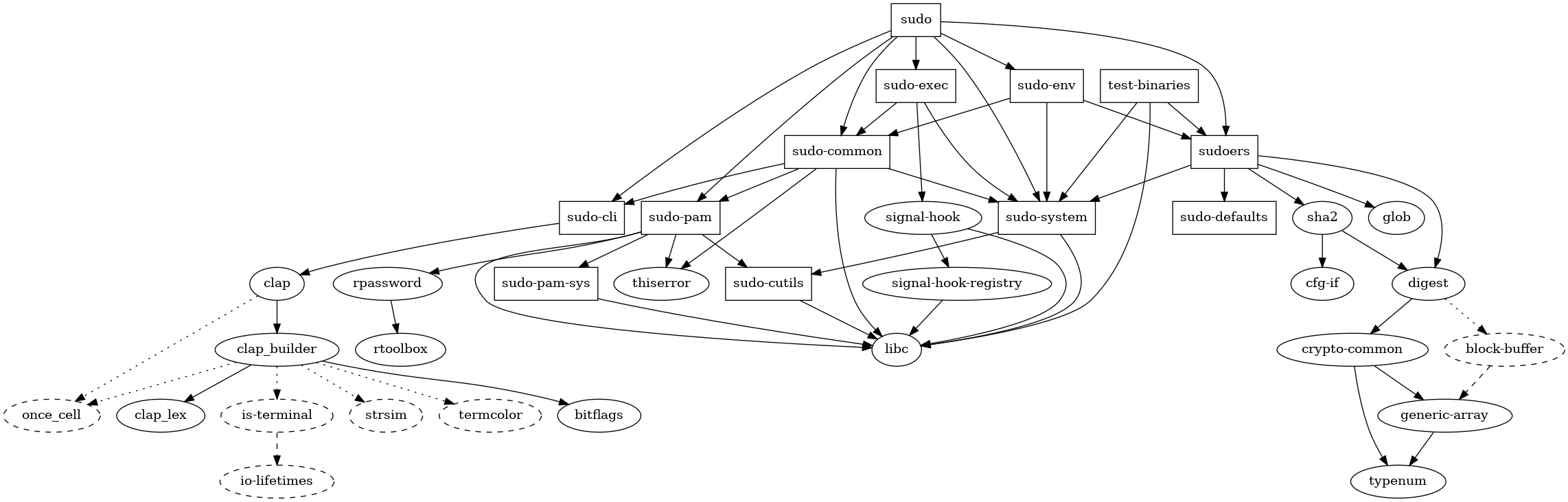

As we ramped up development, we wanted to quickly get to a working prototype. This allowed us to work in more detail on parts of the program, while still being able to quickly run the entire program to validate any changes we made. During this ramp-up, we added approximately 10 direct dependencies, which in turn caused some 125 indirect dependencies to be added to our project. Especially those indirect dependencies might scare you a little for a security-oriented application like sudo-rs, but that number is somewhat artificially inflated because Rust automatically includes all relevant crates for all supported platforms, including crates for platforms such as Windows, which we obviously would not require as a Unix utility.

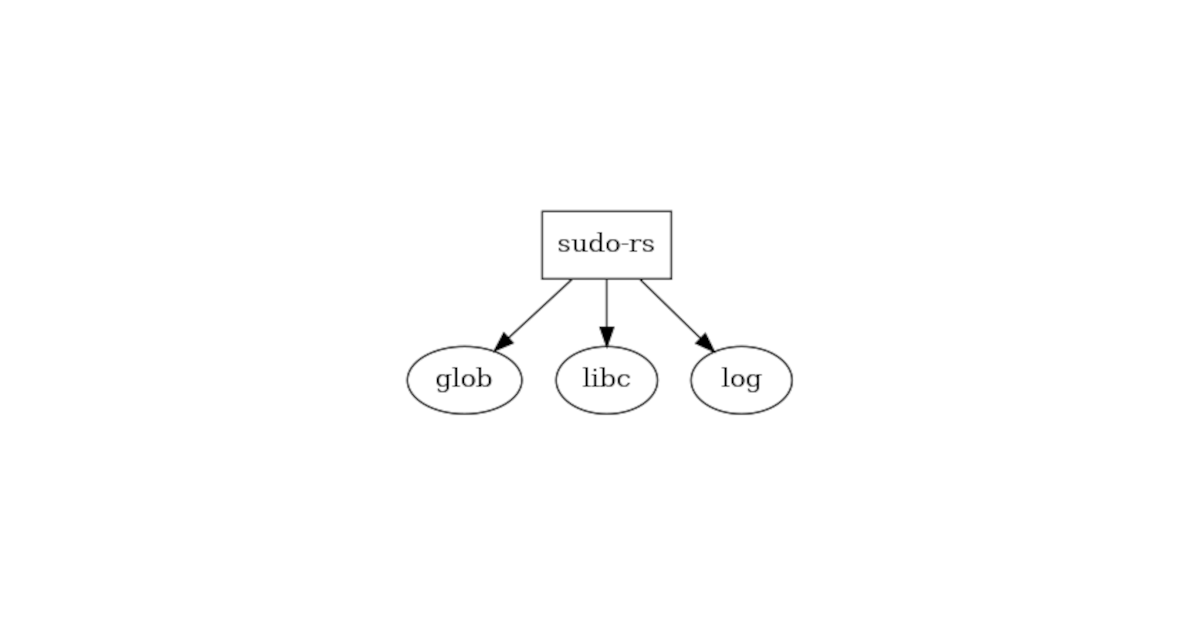

After having identified our dependencies as a potential issue, we started working on reducing our usage of them. Over the course of a few months we carefully removed almost all of our dependencies, ending up with only three crate dependencies required for the current version. Those crates are libc, glob, and log. All three of them are being maintained under the rust-lang github organization, indicating that they are very much at the core of the Rust ecosystem.

Our dependency graph before we finished trimming

Our dependency graph before we finished trimming

Most of the time our usage of the removed crates was limited to a few places and we used little of the functionality of the crate. In other cases we had to put in some more effort, but none of our usage was so extensive that it couldn’t be replaced relatively easily with code written by ourselves.

How dependencies can cause trouble

Sudo-rs team member Marc wrote about dependencies previously on the Tweede golf blog. His post gives a good overview of our considerations concerning which dependencies to keep and which ones to get rid of. In essence, having a lot of dependencies results in two problems. The first is the burden problem, where each added dependency requires extra effort. That manifests in tasks such as keeping up to date with dependencies, but also requires extra work for downstream users like people packaging the project for a Linux distribution.

The second problem is a trust problem: each additional dependency is another team to trust and another codebase to validate. This trust problem is especially important to sudo-rs. As a setuid program meant for elevating privileges, all code that is compiled into sudo-rs has the potential to accidentally (or intentionally) give access to system resources to people who should not have that access. The setuid context additionally puts some constraints on how code is executed, and dependencies might not have accounted for that context. We could not expect any of our dependencies to take into account such a context either.

Of course there is also the other side of the coin: dependencies are not solely a bad thing. As Marc noted in his blog post, we all stand on the shoulders of giants. If we cannot rely on the wider community we might end up repeating mistakes or missing knowledge. We might have to repeat writing code that has already been battle-tested and perfected over many years and by many people. Additionally, being able to contribute back to a wider ecosystem helps everyone, and not just ourselves.

Evaluate and re-evaluate

After announcing the plan to rewrite sudo in Rust, one of the pieces of feedback we read online most was our overreliance on external dependencies, making it harder to validate the correctness of the code. At that time we were already working on reducing our reliance on external dependencies, and those voices confirmed that we were on the right track. While that meant looking critically at our dependencies, it did not mean removing them just for the sake of it. We constantly weighed the pros and cons of each dependency. However, in the end, a lot of the functionality in sudo-rs is of such a special case that we opted to remove all but the most essential crates.

As an example of how we evaluated our dependencies, we previously used clap for command line argument parsing. We replaced it with our own argument parsing once we noticed that adopting clap was taking more code than doing it ourselves. Additionally, we saw that clap offered far more features than we needed, which in turn meant pulling in a significant number of additional dependencies. That resulted in too large of a library, too many teams to trust, and too many possibilities for bad setuid behavior for sudo purposes. In the end, we chose the potential dangers of reimplementing command line parsing over the potential issues of including clap, even though it is a great library for general-purpose command line parsing.

Conclusion

We believe that the current set of crates is a good trade-off between potential risk and gained benefits. Our packaging story is relatively easy for most Linux distributions (with sudo-rs already being available for Debian and Fedora), but that would have been a different story had we kept our 135 dependencies. Also, companies or institutions that require legal review of the entire transitive dependency tree might look at our code much more favorably now. Of course, not every project is like sudo-rs, and other projects might come to different conclusions on how valuable their dependencies are. But halting development, taking a step back, and looking critically at your dependencies is a valuable exercise. Dependencies are often overlooked in that regard, but your responsibility as a developer doesn’t end where your code ends; it extends to your dependencies as well.

Image credits

Both dependency graph images were generated with cargo deb-graph.